The Remembrances of Arthur Cash

with an introduction by Dick Meister

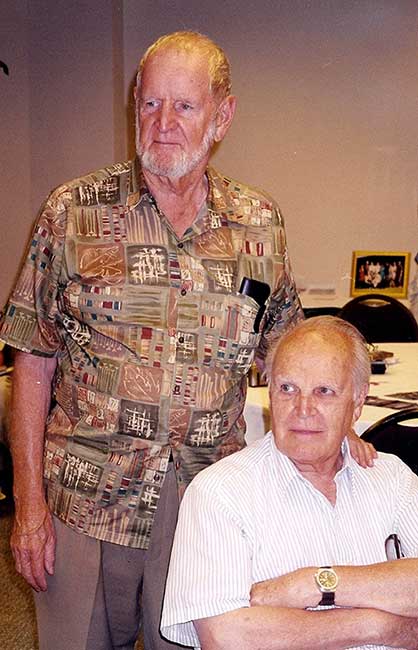

Mitchell and Arthur Cash (c. 2010)

Introduction:

As I was developing the article of Les and Dess Cash, I made contact with Arthur Cash, their youngest son. In response to my letter, Arthur not only answered a number of my questions but also wrote the following remembrances of his youth in Ogden Dunes. In addition he sent a photo of his father and Mitchell in front of Louella Davis’ cottage, near what is today’s Beach Lane and Shore Drive. Arthur also asked his niece Laura Cash Mitchell to send excerpts from her memoirs written by her father, Mitchell Cash. She also shared with the Historical Society a number of family photos. The next issue of “The Hour Glass” will include Mitchell’s remembrances on his summers in Ogden Dunes from 1925 to 1940 and his return with his family to Ogden Dunes after World War II.

The three Cash brothers, Mitchell, Webster, and Arthur, on leaving Ogden Dunes went on to have distinguished careers in the military and in higher education. After the war Mitchell, who had graduated in 1941 with an engineering degree from Purdue University, returned with his family to Ogden Dunes and spent five years as a partner in his father’s construction business, A. L. Cash & Son. The Korean War led to his decision to return to active duty in the Navy. After retiring from a twenty-year career in the Navy, Mitchell went on to have a successful career at NASA.

The middle son, Webster, completed his Ph.D. in International Relations at the University of Chicago with a focus on Africa. He had an impressive career as a faculty member at Fisk University in Nashville, Tennessee and then as an administrator at the Atlanta University Center.

Arthur after a brief career in the theatre served four years in the Hospital Corp of the U.S. Army. In the fall of 1946 he entered the University of Chicago, as a twenty-four year old, married freshman on the G.I. Bill. His love for English literature and research led him to complete a B.A. at the University of Chicago and an M.A. at the University of Wisconsin by 1950 and then a Ph.D. at Columbia University in 1961. In between he taught as an instructor at the University of Colorado for five years. Later he joined the faculty at Colorado State University, living on and working a thirty-acre farm near Fort Collins, with his wife and two children.

With his developing reputation as a scholar, Arthur joined the faculty at the State University of New York at New Paltz in 1967. His scholarly interests had led him to study the life and times of Laurence Sterne, an 18th century English writer. He wrote five major books on Sterne; these were published between 1966 and 1986. Having exhausted the sources on Sterne, Arthur then began to work on Sterne’s close and controversial friend, John Wilkes. This resulted in the publication of John Wilkes: The Scandalous Father of Civil Liberty by Yale University Press in 2006. This widely acclaimed book became one the three finalists for the Pulitzer Prize in biography in 2007. The American Historical Review carried a very favorable review in February 2007. “This book is an elegantly written and meticulously researched biography of eighteenth-century British radical icon John Wilkes. … in vivid detail the story of how an unlikely hero, a flamboyant and scandalous son of the patrician establishment, became an early and powerful advocate of parliamentary democracy and responsible government.” [p. 271] Cash, who served as chair of the English Department SUNY New Paltz from 1975 to 1980, was again appointed chair in the fall of 1995 at the age of seventy-three.

Arthur and Dorothy, the parents of two children, divorced in 1972. Their son, Randall was murdered in 1992 in El Salvador during the peace process that ultimately ended its brutal civil war. In 1979, Arthur married Mary Gordon, who was teaching writing as the community college in New Paltz. Today Mary is an internationally recognized novelist and scholar. Mary Gordon, the McIntosh Professor of English at Barnard College, is known for her short stories, novels, and literary criticism. She is a three-time winner of the O. Henry Award for the best short story of the year. She was also one of ninety-seven prominent Catholics in 1984 who signed “A Catholic Statement on Pluralism and Abortion” calling for a discussion of the Church’s position on these issues. Her book, Reading Jesus, published in 2009, combined her literary training and her study of the gospels. It is worth noting that Arthur has taught the Bible as literature and has written commentaries on the Old Testament and the Epistles for the bulletins of the Episcopal parishes that he has attended.

Arthur, who is now retired from SUNY New Paltz, and Mary have two children. They divide their time between New York City and their country home in Rhode Island. At ninety-one Art remains an active scholar and writer, as well as an involved father and grandfather. He truly has led an interesting life, from directing plays in Juniper Park in Ogden Dunes to being a finalist for the Pulitzer Prize. [Most of the information on Arthur Hill Cash is found on his home page, www.columbia.edu/AHCash-Home]

Ogden Dunes, 1925 – 1939: A Memoir by Arthur H. Cash

When the Cash family came to Ogden Dunes around 1925, the only access road to the lake was what is part of today’s Hillcrest, Ogden, and Cedar Trail. It was surfaced with crushed black cinders from the coke plant of the Gary steel mills. The road ended with a T into a sandy, two-rut road that is now called Shore Drive. Along this yet unnamed road were ramshackle cottages poking out here and there from the second ridge of dunes. In my memory there were only three real houses, I mean houses with concrete foundations, running water, and inside toilets. The Glover and Reck houses [3 Cedar Trail and 4 Cedar Trail] were near the T corner.

The first home built by Samuel Reck in 1924, 4 Cedar Trail

The Glover/Zimmerman Home at 4 Cedar Trail, about 1927

The third house was further to the west was next to Aunt Louella Davis’ cottage. [It was located near what is today the corner of Beach Lane and Shore Drive, possibly 95 Shore Drive.] The owners of the last house were usually absent.

Behind the two homes and the scattered cottages were open, moving dunes and behind them were dunes that had been taken over by oak and cotton wood trees, making a hilly forest sandwiched between sand and the railroad tracks in the south end of town. Other than the town garage near the entrance and the town dump behind it, this land belonged to the goldfinch and the thrush; the rabbit and the fox. Diana of the Dunes (Alice Gray), who had lived in the furthest cottage to the west, was said to run naked over the dunes. Alice died in her cottage, called the Wren’s Nest, on February 9, 1925. So she was gone by the time I got there later in 1925 – when I was three years old. My parents, Dess and Arthur Lester Cash, who lived in Gary, had purchased the most discrepant cottage in Ogden Dunes. We called it “The Shack.”

I remember the day our father took the family to look at the Shack. I went toddling after my two older brothers, Webster, age five, and Mitchell, seven, who ran down the path, across the two-rut road and over the first ridge of dunes with its clusters of tall grasses to the beach and water! Small waves were rolling in leisurely, just barely flooding a wide sandbar near the shore. My mother helped me out to the sandbar where I ran splashing after my brothers.

The man who was selling the Shack was a member of our church in Gary. I think his name was Mr. Todd. He picked me up and carried me down the steep dune just south of the cottage to a deep, quiet woods. When he put me down my feet were soon buried in the cool sand and I was surrounded by tall, mysterious trees. Everything was very green and very still. On one tree clung an upside-down mocking bird which broke the silence with a cat’s meow. Mr. Todd lifted me up to look into the bird’s nest in the fork of a small tree and I could see small speckled eggs. Today’s Hillcrest Road, now the main access road to the lake shore, runs through that valley, but there is a bit of the magic forest still there.

The Shack consisted of one large room and two screened porches. With no electricity, light was provided by oil lamps, a wick burning in a tall glass funnel. The back porch was the kitchen and store room. Here was a small pump about sixteen inches high at the end of a water pipe that thrust itself through the wooden floor. It was painted red and emptied into a large tin pan. A kerosene stove had burners and an oven. The ice box was cooled by a large chunk of ice delivered by a college student on his summer job with the ice man. There was an old fashioned Indiana privy on the dune behind the cottage.

The large, central room had so many beds in it that it wasn’t much fun. My bed was a painted metal crib. As the summers went by I grew so long that I didn’t fit in the crib and had to sleep with my legs bent. When it rained hard, we had to move the beds around and put down pots to catch the water from the leaks. After every rain, dad fixed the leaks, but the next rain brought new leaks.

The fun was to be had on the front porch, where my brothers, parents, and guests played endless games of cards, checkers and dominos. I was usually left out of the games; my brothers decided I wasn’t bright enough to play. It was hot with the heat of the sun bounding off the surrounding sand dunes. Because of that the shade of the porch was magical. Mom brought seemingly endless tall glasses of iced tea and lemonade.

Every spring, dad and the other owners would shovel away the sand that had drifted against the sides of the cottages. On Cape Cod, where I have spent many a summer in recent years, there are old cottages that show only a front face; the rest is covered by sand. The Ogden Dunes dads never left that happen to us.

The road along the shore ended a few yards west of the Shack. From that point, one walked into a world of dunes, open and blowing in the wind, with clusters of trees and grass here and there. How we loved to scramble up those dunes. No one had the concept of dune preservation. We would get above some downward sweep of sand, run and jump as far as we could down the slope, bringing down with us bushels of sand.

We spent long hours on the beach; we boys growing tan and tanner. We got to be good swimmers. I remember mom sitting with other moms, often with a towel around her legs, swatting at flies and laughing. How she loved to laugh. “If you dig straight down” someone would say, “you get to China.” I dug and dug until miraculously in the bottom of my hole appeared water. And sandcastles, an endless sequence of sandcastles. As I grew older, I joined the older kids in walks to the east to Burns Ditch. It was nothing but a ditch through the dunes to drain the low lands to the south for agriculture and industrial development. A big steam shovel threw up sand along the banks to make high ridges on which we hiked. A few years later the Gary Boat Club made it into a marina, but when I was a small kid, it was nothing but a ditch.

Back on the beach we had family picnics, lots of picnics, sitting on old bleached logs, sandwiches wrapped in paper and lots of lemonade. Sometimes we watched the sun set. We could clearly see the tall buildings of Chicago, and the sunsets behind the city were spectacular. All that yellow and gold, someone told us, was caused by the smoke and soot hanging over Chicago.

South from an irregular line of the third ridge of dunes were the woods, dunes that had been conquered by scrub oak, birch, poplar and pine trees and blackberry bushes and wild brush holly. There must have been nature-loving folk who had tramped the dunes before us, because of the paths. I can remember going with my mother and others on explorations, finding wild columbine flowers under the scrub oaks and pines, coming out in a long sweep of sand that began on the highest dune and run down to the low first line of dunes. My mom named that hill the “Mountain.” And she named the paths and others places: the “Punch Bowl,” “Old Baldy.” Once at the top of the “Mountain” a fox darted across our path.

As soon as school opened in late summer, we and most of the families deserted the dunes. As a boy, I wasn’t often there in the winter, but I do remember how the sugar-sand froze as hard as rock. In my teens, after a heavy snow, some of us would toboggan down the “Mountain.” [This dune or a similar one was later called “Suicide.”] Once, when I was twelve, I put on my boots and climbed through the snow to the edge of the “Punch Bowl”, a U shaped ridge with sand (and snow) on one side and a deep ravine on the other in which grew tall trees reaching up for the sunlight, the tallest trees in the dunes. I couldn’t see any human tracks in the snow and it made me happy to think that since autumn I was the only person to stand on that ridge looking down into the shadowy snows inside the bowl.

We saw a lot of Aunt [not by blood, but through friendship and respect] Louella Davis, chief of the admissions office of the University of Chicago. She had grown up with my parents in Marion, Illinois. Aunt Lou had a cottage three doors to the east of the Shack, a larger and better cottage than ours, boasting two rooms, two porches, and a grape arbor. Next to us to the east was another cottage more advanced than the Shack. It had a balcony with two bedrooms, and a larger bedroom below. This palatial structure belonged to the Bill Thompson family of St. Louis. [The senior William Thompson, a successful sales representative for a large utility company, would move his family to Ogden Dunes for the summer while he traveled back and forth on most week-ends.] The Thompson cottage had no electricity with water coming from a large hand pump half way down the hill toward the road. A tin cup hung on the pump, and anyone who was thirsty was welcome to pump the water into the cup. I must have pumped that big old pipe and handle a hundred times. It is burned into my memory. Between Aunt Lou’s and the Thompson’s was the real house that I mentioned earlier, the one with finished windows and a furnace and all that. It had electricity, as did Aunt Lou’s, but the line stopped there.

The Ogden Dunes ski jump was built about the time my folks acquired the Shack [Note: A Norwegian group from of Chicago formed the Ogden Dunes Ski Club and built the tallest man-made ski jump in North America in 1927.] I have a vague memory of watching a jumping competition when I could not have been more than four or five. I think it must have been one of the first of the five annual ski jump competitions that were held before the project went broke and left an unused ski tower zooming up above the dunes. I and my brothers climbed the tower a few times when we were ten or twelve, not going up the steps which we didn’t trust, but crawling up the track down which the skiers came. From the small platform at the top the view was spectacular! Gary and the mills were to our west, endless farms with silos and barns to the south, dunes and wild forests to the east and to the north the lake, the beautiful lake. As soon as word got around that kids were recklessly climbing the ski jump, the town nailed up planks to close the track and passed a law prohibiting climbing. We didn’t think it was reckless; it was just fun.

Dad lost the Shack in the Great Depression. His house-building business in Gary collapsed. We had some rough times, but my parents struggled through. In those years (I was ten, more or less) I continued to spend a lot of time in the Dunes. Aunt Lou would stop in Gary and pick me up and take me for a weekend at her cottage. Her sister Mildred had a daughter Celestine, and they thought I was a good companion for her, which indeed I was. We spent a great deal of time on the beach or at the cottage making fudge. I remember once when I was about eight spending the night at Aunt Lou’s, sleeping on the front porch. A poplar tree stood close to the windows, and even today I can hear in my head its leaves rattling in the summer breeze. Once, against everybody’s advice, I set an alarm clock for five a.m. In the early dawn I dressed myself and went down across the road to the first dune. It was very quiet. The lake was glassy calm. I lay down on the cold sand and watched the curving beach to the east. Then the horizon was on fire, and I saw the brilliant sun rising out of the water.

In early 1930 my dad got the contract to build the Kratz house [today’s 50 Shore Drive], the first house to be built on the first ridge of dunes in Ogden Dunes. No one had ever heard of a house so elaborate or so expensive! I remember a two-inch headline in the Gary Post-Tribune: “Cash Gets Fifty Thousand Contract.” It was in the depression and that house meant work for dozens of men, not only carpenters and plumbers, but truck drivers and lumber yard workers, and many others in a long chain. From then on most of my dad’s building was in Ogden Dunes.

Dad and Nelson Reck, the manager and salesman for Ogden Dunes Realty, were great friends. [Note: When Samuel Reck, the major partner in the Ogden Dunes Realty, retired to Florida his son Nelson took over.] Often on a Saturday dad would drive from Gary to the dunes to meet Nels to plan how they were going to proceed with the development of Ogden Dunes. While the men talked, I was allowed to go off on my own. I always took along my dog Lindy. I was twelve or so, an age of becoming moody and romantic. I recall on one of those Saturdays thinking Jeannie Lauer didn’t love me. I sang a lot of melancholy songs: “Blue Moon, I saw you standing alone, without a dream in my heart, without a love of my own…” I always skipped the last lines because they got too cheerful.

By this time, there were quite a few of real houses in Ogden Dunes and today’s Hillcrest Road and Beach Lane had been built, but most of the dunes were still wild and beautiful. Dad let me take his surveyor’s level, one of those spy glasses on a tripod. I used to leave the tripod in the trunk of the car and take the spy glass. In the woods I would try to watch the birds. Higher up on the dunes, using the level properly, I would measure the relative heights of the dunes. Sometimes I would take a copy of “The Rubaiyat” of Omar Khayyam and sit on the top of the Mountain and read and meditate.

Then we actually moved to Ogden Dunes – mom, dad and I. [It was about 1937] My brothers, Mitch and Web, were in college. [Art continued to attend Horace Mann High School on the Westside of Gary.] The Richardson family, good friends of the Cash family, had a cottage in Ogden Dunes. Olive owned an undeveloped lot at the very top of the second ridge of dunes, across the road from the Kratz house on Shore Drive. In a financial move that avoided many of the disadvantages of the Depression, dad built her a house and then moved his family into it. Miss Olive forgave the rent in exchange for dad’s forgiving her the cost of his own work on her house. The house was one of those simple light-weight concrete block houses with a large picture window looking over Lake Michigan. The view was beautiful. When dad got home from work, he would stand at that window looking at the water: “It’s never the same,” he would say. In 1947-48 he built a similar house a hundred feet further east [44 Ogden Road] on that same dune, and the family moved into that house. A few years later [in 1952], long after I had left home, he sold that house and built another on Beach Lane [29 Beach Lane]. I couldn’t understand why he settled on a house without a view of that every-changing water.

During the summers of the late 1930s, I worked as a common laborer for dad, carrying lumber and digging leach pools and lining septic tanks with brick. On my first day, I was carrying lumber up a plank when one of the men stepped on the plank intending to come down. I said, “Excuse me,” and he got off. When I got to the top, there was dad, standing with his hands on hips: “When you’re on the job, you don’t say ‘excuse me’; you say ‘Get the hell out of the way’! I was shocked; I had never, ever heard my father swear. But I liked it too. I loved most carrying mortar and blocks for Mr. Babilla, the Persian bricklayer who magically could evoke an entire wall. Besides me, there were two other common laborers, brothers, Windy and Lefty. They lived on one of those winding two rut roads on the other side of the highway from Ogden Dunes. Windy was famous for his feats of strength, like lifting the front end of a car so that the wheels left the ground – just for a lark. I worked mostly with Lefty. He had a beat-up Model A Ford in which he would drive me home. We always went for a beer. The bartender could not have cared less that I was underage. How I loved that cool beer after a long sweltering day under the sun. Lefty would tell me about his Saturday nights – nights that he lived for. They consisted, as far as he told me, in taking a date to a dance and getting into a fight. Nothing he enjoyed more than a good fight. What happened later he never said.

When I got home all sweaty and dirty, I would get into my swimming trunks, take a bar of soap, go down to the lake and give myself a bath. I’m sure today I would horrify everybody, but then they thought I was really cute to take a bath in the lake. After my wash, I would run or swim down the beach to join the Thompsons and other teen-age and college-age kids. I was a little contemptuous of them for doing nothing but lie on the beach all day, whereas I was a working man. But I loved the Thompsons, Little Bill, who was very tall and handsome, the age of my big brother Mitch, Mary Jean, who was dark haired and dark eyed, soft and sympathetic, and Joan, a naïve, sweet tempered girl and the beauty of Ogden Dunes beach. Other “working men” would join us, my brother Mitch, Leonard Whelpley, and George Semereau. I was very fond of the Tracht boys, Mel, who was my age, and Vernon his older brother, who was terribly handicapped by a difficult birth. Vernon was the most amusing man I had ever met. He would go on to receive a Ph.D. in Psychology at the University of Chicago and to specialize in the treatment of handicapped children. Then there were other youngsters whose families were vacationing in the dunes, like Mike (Margaret) Breed, whom I sometimes dated. As the sun lowered, we would swim, race and play water games. Bill Thompson taught me how to go really fast under water. Of course, you do a breast stroke under water, but Bill taught me to gather up a leg after each stroke and shove your toe into the sand, and with the next stroke push yourself forward.

Central to our beach life in the late thirties was our raft. I don’t know who built it, but it was a beautiful raft, a ten foot square platform eight inches above the water, carried by empty oil drums underneath. It was anchored, so to speak, by a rope tied to a concrete block. We dived from it, sat on it, sunned on it, told our secrets to each other on it. My mom named us the “rafters”. She called herself a “rafter”. In the morning when the kids were not around, she would put on a big straw had, take a fishing pole and can of worms, push the raft out as far as she could, stand, climb on it, and sit fishing. We had many a meal of very bony lake perch. [The periodic Ogden Dunes newsletter, The Sandpiper, in each issue carried a column on the exploits of the “rafters” prior to the outbreak of World War II. Some were written by Dess Cash; some by Mel Tracht and one was attributed to Art Cash.]

We kids would always pull the raft up on the sand before we went home for dinner. Later we would gather again as the sun began to set. We could always find enough sticks and driftwood to make a fire. Usually somebody brought hot dogs and marshmallows. And we would sing. We had regular songs we sang very night, “Shine of Harvest Moon,” “Dancin’ Tonight,” “Lullaby of Broadway,” “A Tiskit, a Taskit.” About eleven o’clock, sensing some unrecognized communication, we all got up together, brought water to put out the fire, headed for our cars and drove three miles into Miller, Gary’s eastern most neighborhood, for rounds of ice cream cones at Jack Spratt’s.

One night Leonard Whelpley burst into Jack Spratt’s. We had to get to the beach: the raft had come loose and was being blown away by a strong southern breeze. We made a mad dash to the beach. There was a full moon and we could see the raft floating much too far out. We held a brief meeting to make a plan, then to the rescue. The best of our swimmers stripped and went in and swam toward the raft. Bill Thompson got his dad’s outboard motor boat, a very small boat and a very weak motor. He took me and others out. It was very cold. We were stark naked, but into the water we went to push the raft to shore. Ha! It would never have worked had it not been for that little motor boat that Bill tied to the raft. Away it chugged, bringing us ever so slowly to shore. The girls had built a roaring fire, thinking quite rightly that we would be cold. Caught by surprise by these naked men and boys rushing toward their fire, they politely dived behind the log and covered their eyes, so I was told. Now, looking back on it, I think we were very foolish. We were lucky somebody didn’t drown or, in my case, die of exposure. I never have been so cold in my life.

Twice the “rafters” organized treasure hunts. George Semerau and I were appointed to create and supervise the first. The participants were in couples, two couples to a team. There were six teams, each with its own letter name. Each team was given a starting card with instructions of how/where to look for the next clue. The six teams went to six different locations. Team A would, if successful, find a box containing six cards marked for teams A – F. They would take only the A card, leaving the rest to be discovered by the other teams. In that way, we had the teams staggered, going in all directions, and no two looking for the same spot at the same time. The clues were always puzzles, “Go to the Irishman’s detachable shadow.” [This was a trailer that belonged to Joe Mahoney, who lived on the corner of Woodland Trail and where Ski Hill Road begins] Some were written in doggerel verse that George and I made up. Anyway, the first task was to figure out what the message meant, and that took some time. Once understood, the party would roar off in their car to the place and then search all about for the next clue – in trees, under porches, behind bushes. One of our doggerel verses led them to the site of the old ski jump [that had been dismantled in 1937]. One set of cards was in Latin. We had gotten the cooperation of a Professor of Latin who was spending the summer in the dunes. He thought it would be fun helping the teams until he discovered that the hunt went on all night. It actually did last until dawn. The actual treasure was hidden in George’s car; it was a case of beer. The sun was coming up as all gathered at our house, where mom made pancakes for the whole crowd.

The Cash boys had an old car of their own. This fact alone made us glamorous, for it was really cool to have your own “jalopy.” Ours was a 1925 Pontiac with a rumble seat, wood-spoke wheels, engine thermometer on the front of the hood, vertical windshield the top half of which could be opened, and a big wooden steering wheel. Mom named it Napoleon because, she said, it was little but mighty and full of bony parts. (Can you believe it!) It was given to us by Carl, dad’s chief painter, who could not sell it but had to get rid of it because he was going back to his native Lithuania. Dad tried to talk Carl out of going, arguing that they would just grab him and put him in the army. Probably that’s what happened. That part of Europe is where early fighting broke out in 1939. We never heard from Carl again.

There was a little cottage next to a real house, belonging to the Cassidy family [13 Beach Lane]. James Cassidy owned the Federal Bakery in Gary. Dad was his good friend and had built his home and his bakery.

The Cassidy Home built around 1929

The little cottage caught fire one night, caused by spilled kerosene next to the heater. As the fire raged, Harry the Cop ordered me to run back to the town garage for a hose, and I had the distinct pleasure of racing Napoleon as fast its wooden wheels would go up each hill, bouncing down the other side, laying on the “ahooga ahooga” horn at each curve, going lickity split. What a ride! Every Indiana boy’s dream. All to fetch a hose. Of course, it did no good; the cottage burned down anyway. My brother Web and I talked to a very pretty teen-age daughter of the family who had been renting the place, as she stood woefully watching the flames die down. She had lost a ring she had been given by her grandmother. Web questioned her closely about where it had been left? On a dresser. In which room? Where was the dresser in the room? The next day, Web and I put on old clothes, took a couple shovels and went poking through the chard boards and crumpled walls. Behold! We found the ring and returned it to its grateful owner. This and a later fire in 1948 that burned down Marge and Willard Dorman’s large home on Shore Drive led to the organization of the Ogden Dunes volunteer fire department. The prime mover was my brother Mitch, who during his navy service in the war had received some training in fighting fires on ships. When the war was over, he had returned to the dunes and went into business with dad. He became the first fire chief.

In the late summer of 1938 the Rafters organized a hay ride that turned into a disaster. They commissioned Harry Borg, the town marshal, and Ed Moore, a town worker, to organize the ride. They borrowed a long, flat wagon, and loaded it high with hay. I don’t know why they didn’t have horses to pull it, but they didn’t. Instead they pulled it with a tractor. They hung lanterns from the posts at the corners of the wagon. The wagon appeared well lit but had no tail light. I asked Jeannie Lauer if she would be my date, but she declined, as she usually did. I went home and moped and didn’t join the hay ride. I went to bed, but woke up hearing the tense voices of Mitch and dad. “Something has happened”, I said to myself, jumping out of bed. The wagon had been pulled out of the entrance to Ogden Dunes and across the highway onto a wide shoulder of grass. It started eastward toward picturesque Stagecoach Road a quarter of a mile away. Only in one place did they have to pull the wagon so that two wheels were on the pavement, near the grocery and gas station. A truck roared up from behind, and the driver took the lights as something belonging to the gas station. Most of the kids, including Mitch, jumped before the truck hit, but those in front didn’t see it coming. Five or six were seriously injured including Joan Thompson, and Anne North was killed. She was a Northwestern student summering with her older sister, Mrs. Rudolf Kronfeld, in the dunes. Anne was a darling girl, beautiful, intelligent, and good hearted. A few of the families sued the trucking company, but they didn’t have a chance. The law was clear; a vehicle at night must have a red tail light.

As a teen-ager and the only child at home, I found off-season all too quiet. Where there was ice piled up along the beach, I would take the single-shot 22 rifle, and walk the beach shooting at chips of ice that had dared to stick themselves up above all the rest. Mom had made friends with a crow that had been reared near the Kratz home. It came to the kitchen window every day, and mom would feed it scraps. This crow decided to adopt me. When I walked along the beach, it would come along, occasionally swooping down on me and grabbing the hat off my head. Often George Semerau, who was as lonesome as I, would pick me up in his jazzy Buick convertible and we would make melancholy trips to Jack Spratt’s. Sometimes we went high jacking and shooting rats in the old town dump.

Much as I loved working for dad, I knew that building houses was not my destiny. I was not really good at it. Dad once told me that I was the worst mechanic he had ever known. He was wrong; I wasn’t the worst. I’ve been doing household mechanics ever since, but I’m not what anyone would call a good one. I was an actor, the star of Horace Mann High School and the Gary Little Theatre. I was devoted to poetry and Shakespeare, able to recite numerous speeches from the plays. In all of this I was encouraged by my mom, a former high school English teacher, who was also a bit stage-struck. So I was always on the lookout for people who had interests in the arts. A number of professors from the University of Chicago had vacation homes in Ogden Dunes, most of them built by dad. I did what I could to encourage those connections with intellectual or artistic people. Web and I became friends with Mr. Emery Filbey, one of the Vice Presidents of the University and the right hand man to the great Robert Hutchins. [The Filbey home was at 9 Ledge.]

All three of us Cash brothers became close to Mayme Logsdon, the first woman to receive tenure in the Department of Mathematics at the University of Chicago. Dad built a house for her at the crest of Cedar Trail [today’s 49 Cedar] in the mid-1930s. She taught my parents how to play bridge, a game of major importance in their later lives. Professor Logsdon became for us Aunt Mayme. Little wonder that when I was discharged from the army in 1946, having given up my theatrical ambitions, I enrolled in the University of Chicago.

Dad and Mitch watched with great interest the building of the Frank Lloyd Wright house [43 Cedar Trail] in 1940, just below Aunt Mayme’s. Dad thought it unfair that Wright sent in his own crew of workmen to put it up. They never hired a single local workman. The finished house looked wonderful to way it stood against the hill, but inside it did not live up to the great man’s reputation, not at least in my opinion. The two sets of stairs, set in a “V” pattern coming down to the living room were, I thought, pretentious and not very pleasing to the eye. The Armstrong family moved in, and I liked them a lot, especially their black Great Dane.

Frank Lloyd Wright Home, Cedar Trail

Of the people in Ogden Dunes who had some interest in the arts, my favorites were Flora and Rolla Fogarty. Rolla was the chief printer for a publishing house in Chicago that printed mostly educational books. He had begun life as an Irish kid from the Westside of the city; Flora was from an Italian immigrant family in the same area. They were in love with music and poetry and drama and opera and especially Italy, its churches, art and music. Rolla was a trained singer with a beautiful tenor voice and a pianist who composed musical operettas. I first came to admire them when I saw them working on their house [2 Woodlawn Trail]. With their own hands (mostly) they built a house on the top of the dune where the ski jump had stood only a year before. I loved their house. The paintings on the walls were originals; the books were leather bound; they had antique musical instruments and the kitchen was full of exotic Italian food. Flora and Rolla had no children, which may have been one reason they were so good to this kid, Art Cash. They brought me up to date on what interested them, listened to my latest aesthetic theory, and never talked down to me.

Once Rolla organized a sort of festival in which Ogden Dunes citizen of one accomplishment or another performed. It was held in the Frank Lloyd Wright house, making use of the double stairways as the stage. Rolla sang songs from his operetta; my mom read a scene from a Broadway play; others sang or what-have-you. I didn’t have the voice for it, but Rolla talked me into singing that famous song from the Mikado, sung by the Mikado himself, “Let the punishment fit the crime, the punishment fit the crime.”

I was troubled in those years by the disparity in the quality of my life in the dunes and the quality of life of many of my classmates at Horace Mann in Gary. By Gary standards, I was a privileged middle-class kid, but in Gary there seemed to be no barrier between me and the working-class kids like Mel Dupont, Art Kruger, and Jimmy McNamara. Mel and I roomed together when we moved to Chicago right after high school. I was especially bothered that Ogden Dunes admitted no Jews. A lot of my friends at Horace Mann were Jews. Ernie Leiser, the smartest kid in the school, who went on to become a TV correspondent for CBS, was the best friend of brother Web. The sign at the entrance to Ogden Dunes read, “Restricted building sites on Lake Michigan.” Ernie’s folks could not buy a house or a lot in Ogden Dunes. Web and I, who had grown close, confronted Aunt Mayme Logsdon about it. “I know it’s wrong,” she said, “but it works well in practice.” Works well for whom? Web and I asked each other. We knew that there was no respectable answer, and we knew that, for that reason, we ourselves would never settle in Ogden Dunes. Of course all of that was changed a few years later, but too late for us.

On July 4th, 1939, dad took me to the highway and I caught the South Shore for Chicago. On the train I kept thinking about that illustration in my Latin book of some magnificent fountain, under which was written, “The grandeur that was Rome.” To me Chicago was another Rome, grand and open. I could do well there. I loved the dunes, but the promises lay elsewhere, also for my brother Web. He too was in Chicago making his own living, putting himself through the University. He went on to earn a Ph.D. in International Relations and became a professor. And I received a Ph.D. in English from Columbia University, also becoming a professor. We all came back to Ogden Dunes for visits, but the community was never again a significant part of our lives.

Editor’s Note: The next issue of “The Hour Glass” will conclude the story of the Cash family in Ogden Dunes, with excerpts from the “Memoir of Mitchell Cash”.